Functional GI disorders are highly prevalent during the early months, with around 50% of infants suffering from at least one functional GI disorder or related sign or symptom before six months of age4-5. The most common functional GI disorders are infant reflux (affecting around 30% of infants), infantile colic (around 20% of infants) and functional constipation (around 15%)4.

In addition to causing significant distress for infants and families, functional GI disorders also impose a considerable burden on the finances of concerned parents and overstretched healthcare systems. This is in part due to the fact that guidelines, which recommend parental reassurance and nutritional advice, are not always being followed, resulting in some infants being medicated unnecessarily and significant financial costs to the NHS6. Adhering to Rome criteria and NICE guidance can help to ensure optimal diagnosis and management of functional GI disorders.

Diagnosing functional GI disorders in practice

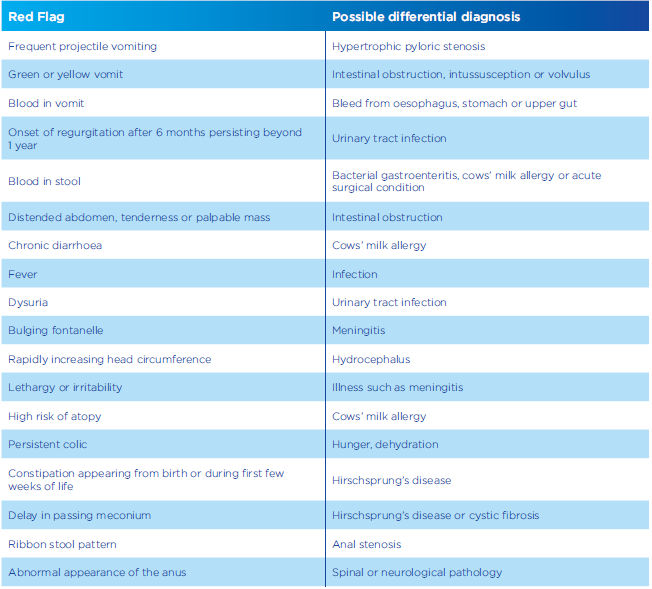

Before diagnosing a functional GI disorder it is necessary to exclude an organic cause for the symptoms. Red flag symptoms and differential diagnoses are listed in Table 1. Infants and children exhibiting these symptoms should be referred to an appropriate specialist.

TABLE 1: Red flags and differential diagnoses7-9

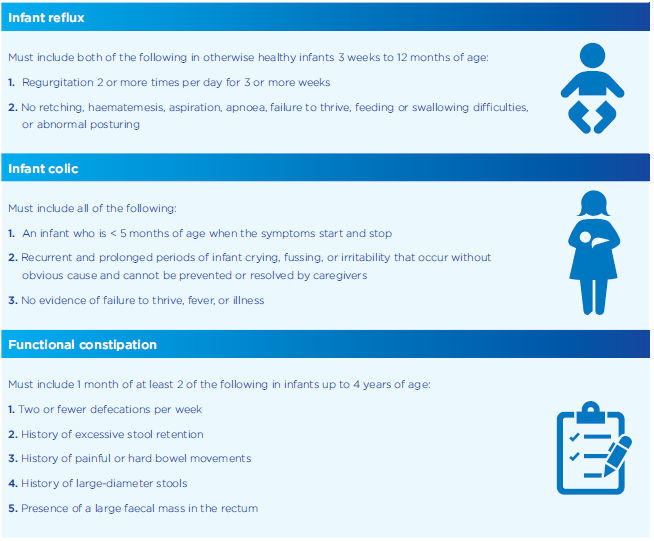

Rome criteria

Internationally agreed criteria for the diagnosis of functional GI disorders, first published in Rome in 1989, have been regularly updated. The most recent version was published in 20161(see Table 2).

TABLE 2: Rome IV diagnostic criteria for infant reflux, infantile colic and functional constipation in infancy; adapted from Benninga, et al1

Delivering effective parental reassurance

Guidance on the management of functional GI disorders from both NICE and ESPGHAN stresses that first-line management should be based around parental support and reassurance7-8-11.

The aim of patient reassurance is to alleviate parents’ concerns about their child’s health and to encourage a change in their behaviour, thoughts or understanding12-13.

Approaches such as the Motivational Interviewing technique — a collaborative, goal-oriented style of communication — can help to ensure that parents are made to feel reassured and confident about the advice they have been given13. This approach involves skilled listening to the parents’ concerns and guiding their actions using expertise when necessary.

The key principles of motivational interviewing are:

- Partnership — working ‘for’ and ‘with’ a parent rather than directing their actions

- Acceptance of the parent’s views and respect for their autonomy

- Compassion — the commitment to pursue the welfare and best interests of the parent

- Evocation — to elicit the parent’s own perspectives and motivations.

Effective use of these principles can help alleviate parental anxiety and discourage the use of inappropriate and expensive medication.

Nutritional and medical management of functional GI disorders

The most important nutritional advice is to support breastfeeding mothers. Breastmilk is specifically tailored to an infant’s developing digestive system and may help to prevent the onset of some functional GI disorder symptoms8-9.

Most guidelines agree that the first-line management of functional GI disorders should focus on parental reassurance and nutritional advice. Indeed, a recent review by Salvatore et al recommended that parental guidance should include advice on feeding volume, frequency, technique for all infants and “consideration of extensive protein hydrolysates or amino acid formulas with proven effect for formula-fed infants with persisting symptoms10.

Pharmacological intervention, whether prescribed or over-the-counter, is of limited use in functional GI disorders and should be reserved for only the most challenging cases10.

Formula-fed infants who suffer from a functional GI disorder may benefit by switching from a standard formula to one specifically designed for the dietary management of the relevant disorder10.

Management of infant reflux

As reflux usually improves spontaneously within the first year of life, the main goal of management is to await this resolution while providing parental reassurance and symptom relief1.

Parents should be offered information on8-9

- The natural history of reflux

Nutritional management should focus on

- Supporting breastfeeding

- Impact of overfeeding on symptoms

- Correcting the frequency and volume of feeds

- The use of thickener or, if formula-fed, thickened or anti-reflux formula9-16

According to NASPGHAN and ESPGHAN, formula-fed infants who fail to respond to non-pharmacological treatment may be suffering from milk protein sensitivity and should be considered for a two-to-four week trial of extensively hydrolysed protein-based (or amino-acid based) formula17.

Pharmacological management is rarely required for infant reflux. NICE advises against the use of PPIs, histamine-2 receptors, metoclopramide, domperidone, or erythromycin, although alginates may be considered in infants showing marked distress if thickened feed has been unsuccessful⁹. NASPGHAN and ESPGHAN advise against chronic use of antacids/alginates in infants and state that proton pump inhibitors should be prescribed at the lowest dose possible and only when there is a clear diagnosis of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD)17.

Management of infant colic

Effective management of colic usually focuses on helping parents cope with the challenge of dealing with a child who cries excessively. They may be relieved to learn that the crying will diminish, usually from around four to six months after birth18.

NICE advises parental education, reassurance and practical tips. Information should be provided on7

- How carers can look after their own wellbeing

- Signs of hunger and fatigue

- Family structure and regularity

- The self-limiting nature of the condition

- Soothing strategies such as holding the baby

- Breastfeeding

Vandenplas et al recommend the following nutritional management11

- If cows’ milk allergy is a potential cause: for breastfed infants, consider the exclusion of dairy products from the mother’s diet or extensively hydrolysed formula for formula-fed infants.

- If cows’ milk allergy is not a potential cause: provide support and encouragement for the mother to continue breastfeeding. For formula-fed infants; a partially hydrolysed, lactose-reduced or lactose-free formula.

Comfort formulas, which contain partially hydrolysed proteins, are specifically designed for the dietary management of colic and constipation.

Pharmacological therapy is not effective in infantile colic and may cause serious adverse reactions11.

Management of functional constipation

Once an organic cause of constipation (such as Hirschsprung’s disease or cystic fibrosis) has been ruled out, management focuses on restoring a regular defecation pattern and preventing relapse. Parents should therefore be offered information on how often they should expect their child to defecate.

Nutritional management focuses on11

- Supporting breastfeeding

- Advising on formula preparation in formula-fed infants

- Considering the use of lactulose, although this may cause flatulence

Juices containing sorbitol, such as prune, pear and apple juice, can help constipation but are not advised as they risk an unbalanced nutrition and may lead to diarrhoea or abdominal pain.

Pharmacological management includes the use of polyethylene glycol in infants over the age of six months¹¹. If this does not work or is not tolerated, NICE recommends the use of a stimulant laxative8.

Do you have a question?

Contact our team of experts for guidance on the use and composition of our product range, for support with queries regarding your Nutricia account and sampling service or to get in touch with your local Nutricia representative. We are available Monday to Thursday 9am-5pm and Friday 9am-4pm (except Bank Holidays)

- Benninga MA et al. Childhood Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Neonate/ Toddler. Gastroenterology 2016;150:1443–1455.e2.

- Kurth E et al. Crying babies, tired mothers: what do we know? A systematic review. Midwifery 2011;27(2):187– 94.

- Vik T et al. Infantile colic, prolonged crying and maternal postnatal depression. Acta Paediatr 2009; 98(8):1344–8.

- Vandenplas Y et al. Prevalence and Health Outcomes of Functional Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Infants From Birth to 12 Months of Age. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2015;61(5):531–7.

- Iacono G et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms in infancy: a population-based prospective study. Dig Liver Dis 2005;37(6):432–8.

- Mahon J et al. The costs of functional gastrointestinal disorders and related signs and symptoms in infants: a systematic literature review and cost calculation for England. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11).

- National Institute for health and care excellence. Colic, infantile. London: NICE; 2017. https://cks.nice.org.uk/colic-infantile [Accessed November 2018]

- National Institute for health and care excellence. Constipation in children and young people: diagnosis and management. London: NICE; 2010. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg99 [Accessed November 2018]

- National Institute for health and care excellence. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in children and young people: diagnosis and management. London: NICE; 2015. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng1/resources/gastrooesophageal-reflux-disease-in-children-and-young-people-diagnosis-and-management-pdf-51035086789 [Accessed November 2018]

- Salvatore S et al. Review shows that parental reassurance and nutritional advice help to optimise the management of functional gastrointestinal disorders in infants. Acta Paediatr 2018; doi: 10.1111/apa.14378.

- Vandenplas Y et al. Functional gastro-intestinal disorder algorithms focus on early recognition, parental reassurance and nutritional strategies. Acta Paediatr 2016;105(3):244–52.

- Linton, et al. Reassurance: Help or hinder in the treatment of pain. Pain 2008;134(1):5–8.

- Miller & Rollnick. Motivational Interviewing: Helping people change, Fifth edition. New York: Guildford Press, 2013.

- Bartick MC et al. Suboptimal breastfeeding in the United States: Maternal and pediatric health outcomes and costs. Matern Child Nutr 2017;13(1).

- Abrahamse E et al. Development of the Digestive System-Experimental Challenges and Approaches of Infant Lipid Digestion. Food Dig 2012;3(1– 3):63–77.

- Vandenplas Y et al. Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux clinical practice guidelines: joint recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2009;49(4):498–547.

- Rosen R et al. Pediatric Gastroesophageal Reflux Clinical Practice Guidelines: Joint Recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2018; [Epub ahead of print].

- NHS choices. Colic. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/colic/[Accessed May 2018].