What are prebiotics and why are they important?

Prebiotics encourage probiotics to flourish; Prebiotic oligosaccharides (OS) are non-digestible carbohydrates which resist stomach acid. They escape digestion and pass into the colon to act as nutrients to the friendly bacteria, or probiotics, that reside there.

Please log in to access this content

Simply log in or register to Nutricia Academy today to access this content as well as a host of other trusted education resources.

Probiotics support the immune system; By attaching themselves to the lining of the gut, probiotics compete with potentially harmful bacteria, thus supporting the immune system.

Breastmilk contains both prebiotics and probiotics; Infants are born with a sterile gut, so probiotic bacteria need to be able to colonise the lower part of their intestines in order to support immunity. Breastmilk is ideally suited to this role as it contains probiotics and prebiotics needed to nurture and feed them.

Other sources of prebiotics; Some infant formulas are supplemented with prebiotics and are therefore beneficial to mothers and babies who are not breastfeeding. Prebiotics are also present in foods such as asparagus, bananas, garlic, chicory, leeks, and tomatoes, as well as some prebiotic fortified cereals.

The role of prebiotics in allergy prevention; Although some results appear promising, questions still remain as to whether prebiotics play a role in the management of allergic diseases, particularly eczema.

More information, including full references, can be found in the full article below.

Introduction

The use of prebiotics in the prevention and management of disease, particularly in formula fed infants, has been much discussed and debated in recent years. However, some healthcare professionals admit to being unclear in terms of what prebiotics actually are; what the difference is between prebiotics and probiotics and how they relate to each other. Healthcare professionals also need information on the implications of prebiotics on infant health and how generalisable the results from clinical trials are. Most importantly, healthcare professionals are faced with the question: ‘Is there clinical evidence to suggest a difference between infant formulas which contain prebiotics and those which don’t?’ and, if so: ‘Which ones and in what format?’. This review aims to address these issues, focusing on the role of prebiotics in the prevention of allergic disease.

Definition

Prebiotics

Prebiotics is a word used to describe a range of non-digestible carbohydrates (also referred to as oligosaccharides or polysaccharides), which resist acid in the stomach and escape digestion by pancreatic and small bowel enzymes in the small intestine1. They therefore pass into the colon in an undigested form and act as nutrients to the bacteria that reside there. However, not all bacteria will benefit from the presence of prebiotic oligosaccharides (OS). Prebiotic OS have a selective role in that they encourage the growth of only the friendly bacteria and cause potentially harmful bacteria to decrease. The most common prebiotics are fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS), galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS), inulin, trans-galacto-oligosaccharides and lactulose (see Figure 1)2.

Figure 1: Sources and examples of prebiotics

| Breastmilk | Human milk oligosaccharides, naturally present in considerable amounts in human milk |

| Infant milk formulas | A GOS/FOS mixture, and GOS alone are added to some infant milk formulas |

| Asparagus, bananas, garlic, barley, chicory, onion, artichokes, leeks, and tomatoes | Inulin is a naturally present oligosaccharide in these foods |

| Breakfast cereals | Some cereals contain prebiotics and fibre |

| Medicines | Lactulose |

Prebiotics are non-digestible carbohydrates that are food for the friendly bacteria naturally found in the gut that stimulate their growth and activity3.

Probiotics

The colon is home to a vast population of bacteria, many of which perform vital functions. Amongst these are several species of so-called ‘friendly bacteria’. These friendly bacteria, also referred to as probiotics, include bifidobacteria and lactobacillus species4.

Prebiotics and probiotics are therefore inter-dependent; the former encourage the growth of the latter, while the latter depend on the former to flourish.

Background

The origin for studying prebiotics lies within the “hygiene hypothesis”. This hypothesis proposes that a healthy gut may lead to a healthy infant free from disease, in particular allergic disease. This hypothesis was originally proposed by Strachan in 19895. Since then, a number of epidemiological studies have supported these findings. Those that particularly indicated the importance of prebiotics and probiotic bacteria showed that:

- a diet rich in fermented vegetables may lead to lower levels of food and other allergies6;

- the presence of healthy gut flora, i.e. healthy gut bacteria consisting of lactobacillus and bifidobacteria, lead to fewer allergic diseases7;

- the use of antibiotics before the age of 2 years, killing off beneficial bacteria, has been linked with an increase in allergic disease8.

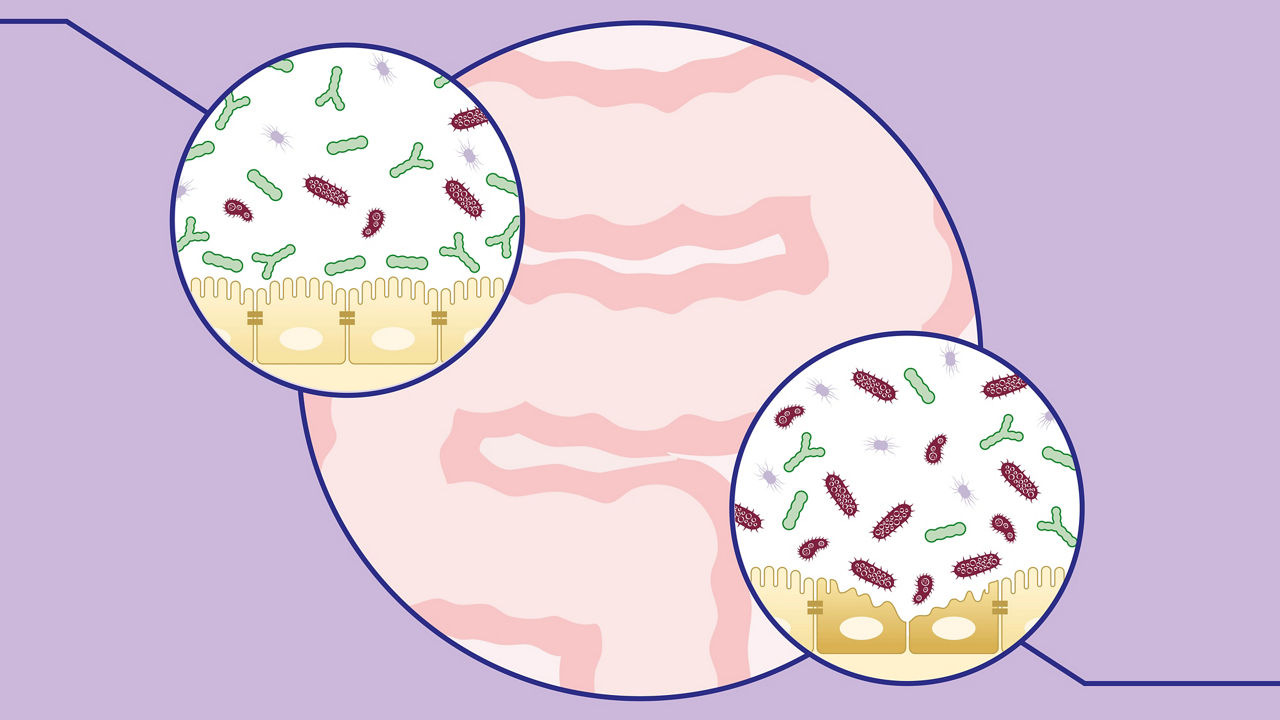

Probiotic bacteria play an important role in the immune system provided by the gut as they compete with potentially harmful bacteria to attach themselves to the lining of the gut, thus preventing infection. These probiotic bacteria also encourage cells lining the gut to produce more and thicker ‘mucous’ which stops harmful bacteria getting into the blood stream and the rest of the body9. However, infants are born with a sterile gut which then becomes colonised by probiotic bacteria in early life.

Breastmilk is ideally suited for this role as it contains both probiotic bacteria10 and the nutrients (human milk oligosaccharides11/prebiotic oligosaccharides) needed by probiotics, together with other nutritional and immunomodulatory factors (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Immunomodulatory components of breastmilk17

| Anti-microbial compounds | Immune compounds |

|---|---|

| Immunoglobulins | Macrophages, neutrophils, lyphocytes |

| Proteins e.g. Lacto-ferrin | Cytokines |

| Antibodies | Growth factors |

| Oligosaccharides & prebiotics | Hormones |

| Long chain fatty acids | |

| Nucleotides | |

| Anti-inflammatory compounds | |

| Cytokines | |

| Adhesion molecules | |

| Long chain fatty acids | |

| Hormones | |

It is well known that the faeces of breastfed infants contain more “friendly” bacteria than those of formula fed infants and this difference persists well into infancy13;14. However, some women either cannot or choose not to breastfeed. In an attempt to ensure colonisation of the infant’s gut with probiotic bacteria, supplementation with prebiotic OS15 in early life has been explored.

What are the health benefits of prebiotics?

Nine studies are cited in the literature that have investigated the effect of different types of prebiotic OS supplementation in infants. These studies showed that, depending on the age of the infant and the prebiotic OS used, effects may be seen on immune cells16;17, in particular on IgE levels18. Results on the prevention and management of diarrhoea and constipation are varying with four13;19-21 out of six13;16;19-22 studies showing positive results. The role of prebiotics in reducing respiratory tract infections, fever and use of antibiotics also looks promising with fewer infections19;23, reduced use of antibiotics19;20;24,25 and reduced episodes of fever20;24;25 seen in formula-fed infants supplemented with prebiotic OS than those who did not receive any supplementation.

Effect of prebiotics on the reduction of allergic diseases

It is established that allergic diseases such as asthma, rhinitis and eczema are increasing in both the developed26 and developing27 world. Taking into account the role of gut bacteria in the immune system, differences in gut bacteria seen in allergic and non-allergic infants28 and the role of breastmilk in nurturing healthy gut bacteria, researchers have studied various mixtures of oligosaccharides to mimic the human milk oligosaccharides profile and hence its bifidogenic factor.

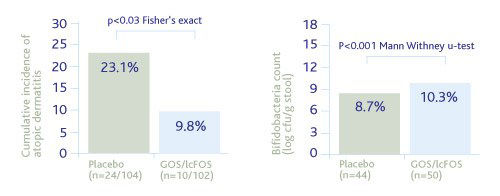

One study is cited in the literature using a specific mix of prebiotic GOS/FOS added to a hydrolysed whey formula13,24 in young infants at high risk of developing allergic diseases. In this study, 9.8% of children receiving the prebiotics developed eczema, compared to 23.1% in the placebo group at six months of age (Figure 3)13. Follow-up of these infants at 24 months (n=134) showed a long lasting effect of the prebiotic OS supplement. In the prebiotic OS group, children were significantly less likely to suffer from eczema, recurrent wheezing and allergic urticaria24. Follow-up in this study was continued beyond the intervention period until 5 years of life, involving a total of 92 children (50 in the placebo group and 42 in the oligosaccharide prebiotic intervention group)25. The significant protective effect was found to last beyond infancy until 5 years of life for any allergic manifestation and atopic dermatitis (cumulative incidence: 30.9% vs. 66% p<0.01) and 19.1% vs. 38%, p<0.05) and allergic rhinoconjunctivitis (prevalence at 5 years 2.4% vs. 14%, p=0.05). Although the prebiotic intervention group had 75% reduction in the prevalence of persistent wheezing (4.8 vs 14 %), no significance was shown.

Figure 3: Incidence of atopic dermatitis in GOS/FOS and placebo at 6m and 5yrs*

*Adapted from Moro G et al 200613 and Arslanglo et al 201225

Results from this study indicate that the long-term protective effect of these different prebiotic mixtures relate to an early immune modulating effect through modification of the gut bacteria as the principal mechanism of action. Central to these findings, however, is that the effect seen with supplementation of prebiotics is specific to the dose and mixtures used and data cannot be extrapolated to any other source of prebiotics.

The question then arises of how applicable and generalisable the findings generated from these studies are to term infants without a family history of allergy and when added to a standard cows’ milk formula.

This was addressed by the Multicentre Immuno-Programming Study (MIPS) which included 7 centres across 5 countries in Europe (presented by Christophe Gruber, British Society of Asthma and Clinical Immunology Meeting, July 2009). This study aimed to look at the prevalence of eczema in 1130 unselected infants randomised on an unmodified formula containing prebiotic OS (active group) or without (control group) against a reference group (breastfeeding only). The prevalence of eczema was significantly lower in the active group at 16, 24 and 52 weeks than in the control group. The severity of eczema was also significantly lower in the active group than in the control group. However, no difference was seen in colic, cramps, nappy rash and wind between the groups studied.

In support of these findings, Ziegler et al.29 showed that polydextrose, galacto-oligosaccharides and lactulose (8g/l) added to a standard cows’ milk formula significantly reduced the prevalence of eczema in an unselected population.

In summary, the human gut and, more precisely, the gut bacteria (probiotics), plays a central role in preventing allergic diseases. Prebiotic OS provide the required nutrients to these probiotics. Prebiotics are naturally found in breastmilk, explaining the higher levels of probiotics (lactobacillus and bifidobacteria) seen in the stools of breastfed babies compared to formula fed babies. In the past two decades, researchers have investigated the effect of using different types of prebiotics in infants and promising effects on colonisation of the gut with probiotics, reduced episodes of diarrhoea/constipation, respiratory infections and fever and less frequent use of antibiotics have been reported. The most promising effect of prebiotic OS supplementation in early life is the long-term prevention of allergic symptoms using a particular mixture of GOS/FOS. While clinical evidence continues to accumulate in support of these findings, questions remain as to whether the effect in allergy prevention trials seen are replicable and if there is a confirmed role for prebiotics in the management of allergic diseases, particularly eczema.

About the author

Dr. Carina Venter, NIHR Post Doc Research Fellow, University of Portsmouth Senior Allergy Dietitian, The David Hide Asthma and Allergy Research Centre, Isle of Wight.

Opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily those of the publisher or editorial staff.