How to support breastfeeding mothers

This article first appeared in the Journal of Family Health Care www.jfhc.co.uk, and is reproduced with the Journal’s and author’s permission. With the right level of advice and support from health professionals, it is possible to encourage more mothers than ever to breastfeed, believes Dr Sue Battersby, an independent researcher, lecturer and author in infant feeding. Here she offers some vital tips.

Please log in to access this content

Simply log in or register to Nutricia Academy today to access this content as well as a host of other trusted education resources.

Introduction

Breastfeeding has become an important public health issue because of the increasing knowledge of its short and long term benefits, both for mothers and infants. Breastfeeding is seen as the best form of infant nutrition, and the World Health Organization (WHO) and Department of Health (DH) recommend that infants should be exclusively breastfed for the first 26 weeks of life. From around 26 weeks it should continue with appropriate types and amounts of solid food1,2. To enable these aims to be met, local, national and international strategies have been developed to support and promote breastfeeding over the last few decades.

The DH included breastfeeding in their Operational Plan 2008/09–2010/113.

Along with the already existing aim to increase the initiation of breastfeeding by 2% per annum, they wish to see an increase in the percentage of infants breastfed at 6 to 8 weeks.

Despite public health initiatives, many mothers do not breastfeed for as long as recommended. Although the majority of new mothers in England do breastfeed their infants from birth (76%), the number rapidly declines to 63% at 1 week. Six weeks after birth, only 21% of mothers are still exclusively breastfeeding, as many have introduced their infants to formula by this stage4. Given these figures, health visitors, midwives and other healthcare professionals have an important role supporting mothers in initiating and continuing breastfeeding.

Question 1: Why is breastfeeding important?

Breastfeeding confers benefits to both mother and baby. Although the benefits of breastfeeding are greater in developing countries, there are still demonstrable benefits to be gained in industrialised countries5. Breastmilk provides the optimal nutrition for infants whilst enhancing immunity. It helps reduce the risk of infections, particularly gastroenteritis, respiratory infections and otitis media and it can also decrease the risk of diabetes6. Further, it lessens the risk of mortality from necrotizing enterocolitis and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS)6.

For mothers, breastfeeding reduces the risk of maternal breast and ovarian cancer and decreases the risk of hip fractures after the age of 656. The benefits are dose related, therefore the more exclusive and longer the breastfeeding the higher the overall benefits7.

Question 2: What is breastmilk?

Breastmilk is a unique substance: it is produced by the mother to meet the individual infant’s nutritional requirements but it also contains numerous immunological factors, digestive enzymes, hormones, growth factors and transfer factors which are all vital for the immune system and other body functions8. Colostrum is the important first milk. This changes to mature milk between the third and fourth day. The quantity and quality of milk varies during a feed, from feed to feed and from day to day, ensuring the infant’s nutritional requirements are adequately met.

Following the delivery of the placenta the mother’s progesterone level falls, enabling prolactin levels to rise and initiate milk production. During the first 2 days following birth lactation is hormonally driven. However, from day 3 this changes, when milk removal becomes essential for the successful continuation of lactation9. As the infant suckles, prolactin and oxytocin are released, which produce and expel milk from the breast, respectively. Milk is then produced on a supply and demand basis: restricted or ineffective suckling will cause the Feedback Inhibitor of Lactation (FIL) to come into play, and milk production will be reduced.

Question 3: What are the main reasons why mothers discontinue breastfeeding?

The reasons why mothers discontinue breastfeeding are varied. They can include physical, psychological, social, medical and baby-focused reasons. Many mothers discontinue long before they had originally intended. The most common reasons for discontinuing are insufficient milk (39%) and the baby rejecting the breast (20%). These are closely followed by painful breasts and/or nipples (14%)4. All these are issues that could be resolved with appropriate information and support.

Question 4: When should the baby be fed?

Breastfeeding and milk supply work best when feeds are not timed. Ideally breastfeeding should be baby-led. The term “baby-led” has replaced the term “demand feeding” because the latter may lead to the perception that breastfeeding is inherently demanding. Health professionals should not specify time scales, as patterns of feeding vary between infants and with age.

Mothers should be encouraged to feed their infants when they show signs of hunger. These begin with opening of the mouth, sucking noises, searching for the nipple, tongue movements, eyebrows furrowing and tension in the face. This is followed by clenching and unclenching of the fists, flexing of the arms, hand to mouth movements, increasing restlessness and finally crying10. Both breasts should be offered at each feed although the infant may only take the first.

Question 5: What is the recommended breastfeeding position?

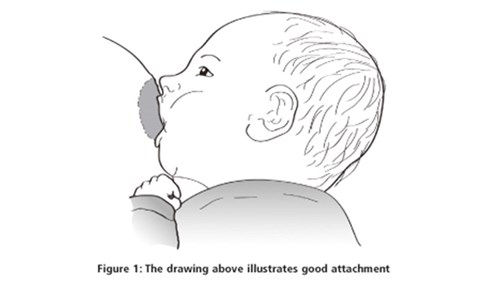

There is no correct position for breastfeeding, however there are principles of good positioning and attachment which should be explained to the mother.

The mother should be encouraged to adopt a comfortable position for feeding. The infant’s head and body should be in a straight line and the whole body should be turned and held closely to the mother’s body.

The infant should face the breast with their nose opposite the nipple. When the infant’s mouth is wide open the infant should be brought to the breast gently but quickly, aiming the bottom lip and chin as far away as possible from the base of the nipple and the nipple should be aimed towards the roof of the infant’s mouth (see figure 1). As the infant attaches the mother may feel a strong drawing sensation which should only last for a few seconds.

Question 6: How can I encourage good attachment, and look out for bad attachment?

A good personal understanding of positioning and attachment will enable the health care professional to facilitate good attachment. Good attachment can be assisted by providing information and instruction to mothers in the antenatal period, immediately following the birth of the infant and in the early postnatal period. Feeding should be observed in the early postnatal period or whenever problems occur to see if poor or suboptimal attachment is occurring. The mother should be taught to recognise the signs of good attachment and if incorrect attachment occurs the mother should be taught how to reattach the infant at the breast. When correctly attached, there should be no pain when feeding.

Question 7: How can breastmilk be expressed and stored?

During the antenatal or early postnatal period all mothers should be shown how to hand express as a self help tool11. A mother should ideally wait until breastfeeding is established12, i.e. after 10–14 days before expressing so that others can feed the infant. Milk can be expressed by hand or by pump but all equipment must be sterilised and good hand hygiene observed. The duration and timing for expressing will depend upon the mother’s routine13. It is best to use fresh expressed milk as freezing results in a gradual decrease in breastmilk leucocytes and immunoglobulins which can lead to reduced antibacterial activity over time14. The milk can be stored as detailed in table 1. Frozen milk should be defrosted in a fridge or in a jug of warm (not hot) water and never in a microwave.

Table 1: Maximum storage times for expressed milk (www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/PH011guidance.pdf) Up to 5 days in the main part of the fridge, at 4°C or lower Up to 2 weeks in the freezer compartment of the fridge Up to 6 months in a domestic freezer, at minus 18°C or lower |

Table 1. Source: NICE. Improving the nutrition of pregnant and breastfeeding mothers and children in low-income households. NICE PH11. London: NICE, 2007)

Question 8: How should women be advised to deal with sore nipples from breastfeeding?

Sore and cracked nipples can result in severe pain for the mother and an unsettled baby. As with all breastfeeding problems a mother may encounter, the best method is to take a problem solving approach which involves listening to the mother carefully, taking a feeding history and observing a feed before offering information on appropriate solutions and alternatives thus enabling a mother to make her own decisions15. The most common cause for sore nipples is poor or suboptimal attachment which can be exacerbated by incorrect positioning, engorgement or tongue tie. Helping to improve positioning and attachment is the main line of treatment. Other suggestions include gently applying expressed breastmilk (EBM) after feeding, wearing a soft cotton T-shirt instead of a bra for a while and avoiding the use of soap.

Question 9: What is mastitis and how can it be addressed?

Mastitis is inflammation of the breast and can be infective or non-infective. If untreated non-infective can become infective and even form an abscess. It presents as a red, painful area of the breast, either localised as a wedge or over the whole breast. It is usually accompanied with aching flu-like feelings and even rigors. A problem solving approach, as detailed in question 8, should be taken to identify the possible causes. The treatment includes gentle massage of the affected area whilst feeding, good positioning and attachment, expressing after feeds to drain the breast if necessary, as much rest as possible and anti-inflammatory drugs i.e. Ibuprofen. It is imperative that the mother keeps feeding and if the symptoms do not improve within 12–18 hours antibiotics may be necessary12.

Question 10: How can health professionals encourage and support breastfeeding mothers?

All health professionals caring for breastfeeding mothers should ensure they have training in the practical management of breastfeeding support and maintain this knowledge16. Support for breastfeeding should begin during the antenatal period and involve fathers whenever possible. Mothers should be informed of the benefits and the management of breastfeeding. This will assist them to make an informed choice and help them with breastfeeding in the early postnatal period17. They should also be given contact details of where to seek help and support should they need it.

- World Health Organization [WHO]. 54th World Health Assembly. Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding: The optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Geneva: WHO, 2001.

- Department of Health [DH]. Infant Feeding Recommendations. 264898 1p 70k. London: DH, 2004.

- Department of Health. Operational plans 2008/09 – 2010/11 (Implementing the 2008/09 Operating Framework) National Planning Guidance and ‘Vital Signs’. London: DH, 2008.

- Bolling K, Grant C, Hamlyn B et al. Infant Feeding Survey 2005. London: The Information Centre, 2007.

- Agostoni C, Braegger C et al. Breast-Feeding: A commentary by ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 2009;49:112-125.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Breastfeeding and maternal and infant health outcomes in developed countries. AHRQ Publication No. 07-E007, 2007 http://www.ahrq.gov/downloads/pub/evidence/pdf/brfout/brfout.pdf[Accessed February 2011].

- UNICEF UK Baby Friendly Initiative. Baby Friendly statement on new breastfeeding research. 2010. http://www.babyfriendly.org.uk/items/item_detail.asp?item=620 [Accessed January 2011].

- Royal College of Midwives [RCM]. Infant feeding: a resource for health care professionals and parents. London: RCM, 2009.

- Jones E, Spencer SA. The physiology of lactation. Paediatrics and Child Health 2007;17(6):244-248.

- La Leche League. Caesarean birth and breastfeeding. Leaflet no 0744. 2005.

- BFI. Best Practice in Maternity Services: Step 5. 2006. http://www.babyfriendly.org.uk/page.asp?page=65 [Accessed January 2011].

- Abbett M. A mother’s (and others) guide to breastfeeding. 8th issue. Nottingham: RL Advertising, 2008. www.mothersguide.co.uk [Accessed January 2011].

- Medforth J, Battersby S, Evans M, March B, Walker A et al. Oxford Handbook of Midwifery. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Friend BA, Shahani KM, Long CA, Vaughn LA. The effect of processing and storage of key enzymes, B vitamins, and lipids of mature human milk. 1. Evaluation of fresh samples and effects of freezing and frozen storage. Pediatric Research 1983;17(1):61-64.

- NHS Sheffield. The Sheffield Infant Feeding Guidelines: For Health Professionals. 2009

- Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN). Infant feeding survey 2005: A commentary on the infant feeding practices in the UK. Position statement by the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition. London: The Stationary Office, 2008.

- BFI. Best Practice in Maternity Services: Step 3. 2006. http://www.babyfriendly.org.uk/page.asp?page=63 [Accessed January 2011].